Conclusion

Sample Acquisition

Tissue Preparation

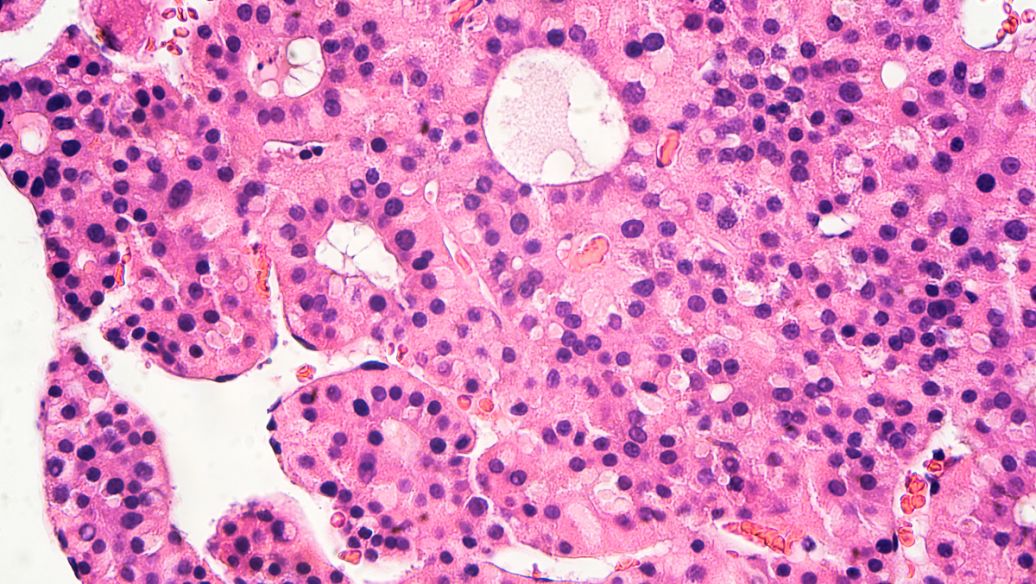

small cell liver cancer

Cell Isolation and Purification

Cell Seeding and Culture Initiation

|

Culture Vessel

|

Suitable for

|

|

Culture Flasks

|

General cell culture, especially when a larger volume of cells is needed

|

|

Multi – well Plates

|

High – throughput experiments, such as drug screening

|

|

Petri Dishes

|

Simple cell culture and observation, suitable for smaller – scale studies

|

Preparation of Culture Medium

Incubation and Culture Maintenance

Cell Sub – Culturing

Cell Characterization and Analysis

References and further readings:

1.Kapałczyńska, M., Kolenda, T., Przybyła, W., Zajączkowska, M., Teresiak, A., Filas, V., … & Lamperska, K. (2018). 2D and 3D cell cultures – a comparison of different types of cancer cell cultures. Archives of Medical Science, 14(4), 910–919.

https://www.termedia.pl/Journal/-19/pdf-28752-10?filename=2D%20and%203D.pdf2.Thoma, C. R., Zimmermann, M., Agarkova, I., Kelm, J. M., & Krek, W. (2014). 3D cell culture systems modeling tumor growth determinants in cancer target discovery. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 69–70, 29–41.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0169409X140003503.Kim, J. B. (2005). Three-dimensional tissue culture models in cancer biology. Seminars in Cancer Biology, 15(5), 365–377.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1044579X05000301

FAQ

What are the common challenges in culturing cancer cells?

- Contamination: Bacterial, fungal, and mycoplasma contamination can easily occur during cell culture, which can affect the growth and behavior of cancer cells. To prevent contamination, strict aseptic techniques should be followed, including working in a laminar – flow hood, using sterile equipment and reagents, and regularly testing for contamination.

- Difficulty in establishing cell lines: Some cancer cells may be difficult to culture in vitro, and establishing a stable, immortalized cell line can be challenging. Factors such as the origin of the cancer (e.g., some types of cancer may have unique growth requirements), the presence of normal cells in the sample, and the genetic instability of cancer cells can contribute to this difficulty.

- Phenotypic and genotypic changes: Over time in culture, cancer cells may undergo phenotypic and genotypic changes. This can lead to a divergence from the original tumor characteristics, which may affect the relevance of the cultured cells in representing the in – vivo situation. To minimize these changes, cells should be used at early passage numbers and maintained under optimal culture conditions.

Can cancer cells from different sources be cultured using the same method?

- Authentication methods such as short tandem repeat (STR) profiling can be used to verify the identity of cultured cancer cells. STR profiling analyzes specific regions of the cell’s DNA to create a unique genetic fingerprint, which can be compared to known profiles of the original cell line.

- Checking for the presence of cancer – specific markers, both at the protein and gene levels, can help confirm the authenticity of the cultured cells.

- Regular monitoring of cell morphology and growth characteristics can also provide clues about the integrity of the cell culture. If there are significant deviations from the expected phenotype, further investigation may be warranted.

What is the significance of 3D culture of cancer cells compared to 2D culture?

- In 2D culture, cancer cells grow on a flat surface, which may not fully mimic the complex in – vivo environment. In contrast, 3D culture systems, such as using hydrogels or scaffolds, allow cancer cells to grow in a more physiologically relevant three – dimensional structure.

- 3D – cultured cancer cells can better recapitulate cell – cell and cell – extracellular matrix interactions, which are important for understanding tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis.

- They can also be more representative of the in – vivo drug response, as the diffusion of drugs and nutrients may be different in 3D compared to 2D cultures. This makes 3D culture a valuable tool for more accurate pre – clinical drug screening and cancer research.

How long can cancer cells be cultured in the laboratory?

- Some cancer cells can be cultured for an extended period, and with proper cryopreservation techniques, they can be stored for years. Immortalized cancer cell lines, which have acquired the ability to divide indefinitely, can be continuously sub – cultured as long as the culture conditions are maintained.

- However, the growth characteristics and genetic stability of the cells may change over time. For primary cancer cell cultures, which are directly derived from patient tissue, they may have a more limited lifespan in culture, typically several passages, as they are more representative of the original tumor but also more sensitive to changes in the culture environment.

Leo Bios

Hello, I’m Leo Bios. As an assistant lecturer, I teach cellular and

molecular biology to undergraduates at a regional US Midwest university. I started as a research tech in

a biotech startup over a decade ago, working on molecular diagnostic tools. This practical experience

fuels my teaching and writing, keeping me engaged in biology’s evolution.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *